platform_as_a_curatorial_research_lab_for_independent_curators

curatorial practice

Seen but unnoticed. Bodily infrastructure at work

curator_ Sofía Dourron

In the introduction to Extrastatecraft. The Power of Infrastructure Space1 Keller Easterling makes it very clear: infrastructure is not and never has been just the buildings, highways, transport systems, communications networks, electric grids and pipelines that allow our bodies to move, interact and generally function within the confines of finite spaces. Infrastructure includes “pools of microwaves beaming from satellites and populations of atomized electronic devices that we hold in our hands” but also the “shared standards and ideas that control everything from technical objects to management styles”. Operational protocols, public policy, and behavioral guidelines are forms of infrastructure that make our lives possible as much as they inform the way we live and how we relate to each other, the world around us, and our own bodies. Infrastructure is all that, even in the tiniest most imperceptible ways, makes any sort of action possible. It is the invisible support for life itself. However, such hidden organizational substrate is not as hygienic and neutral as its inherent invisibility makes it appear; on the contrary, it carries ideologies, biases, values, it defines what actions are desirable in specific situations and which ones are not, it dramatically narrows the possibilities of inter, or most probably, in Karen Barad’s words, intra-action2. In the present, as Easterling declares: “Far from hidden, infrastructure is now the overt point of contact and access between us all—the rules governing the space of everyday life.” As such, it inevitably leaves traces in our bodies, our gestures, and our behaviors. Layers of repetition that accumulate over time in bones and tissues, in memory and identity.

Art operates as an interlocked system both within general material and immaterial infrastructure, and bounded by its own set of infrastructural models, whether formal or informal, sophisticated or precarious. But, however constrained by the dominant logics and logistics produced in the name of the “contemporary”, due to its ability to thrive in contradiction, it still seems to carry the most potential to disrupt the flow of actions these models produce, as well as to produce alternative and more flexible configurations beyond its own limits of action. This project investigates ideas of the body in relation to infrastructure: its operations as a support system itself, and its multiple interactions with other forms of infrastructure. It gathers a series of works that deal with bodies as system for the circulation of affect as well as a vehicle for physiological functions in close and emotional collaboration with technological devices, the entanglement of the senses with infrastructural spiritual paradigms, and disturbed modes of interacting with spatial limits and unspoken rules of functionality. Seen but unnoticed. Bodily infrastructure at work proposes to take another look at how our bodies and subjectivities interact with their surroundings, whether material or inmaterial, through four different and somewhat absurd strategies.

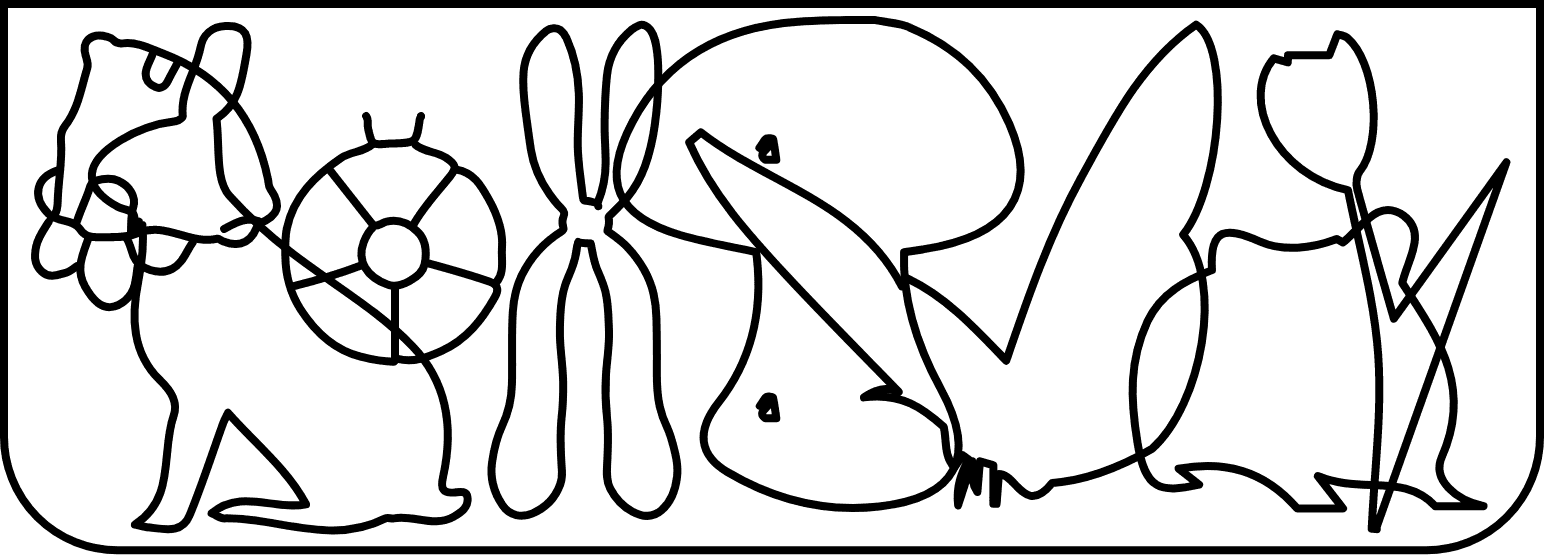

Yun Choi, Doomsday, video, 2020

Holding hands… telepathically

In 2020, during the Covid-19 lockdown, artist Yun Choi, at the time based in Seoul, found herself, like most of us, physically limited by the health and security guidelines implemented by her country. She was highly connected through screens and a myriad of digital platforms and devices, but physically, and often emotionally, detached from other human beings due to border shutdowns and social distancing. The protocols that kept us safe and protected, individually and collectively, also kept us apart from one another. Immersed in this context, with a looming apocalypse in the shadows, Choi created an on-going fictional archive that re-imagined the notion of protocols and infrastructure in a series of collaborative works titled <b>Doomsday</b>. She sent a series of instructions and tasks to seven friends, all women, who live and work in different parts of the world, in order to create new forms of connection, rethinking solidarity and affectivity through unexpected forms of infrastructure such as telepathy, hands spas, and songs handed down by oral tradition. In the<b>Doomsday video</b>, she created a parallel reality from the fragments of the participants experiences, traditions, imaginations, backgrounds, and physical realities. All these scraps collected from their smartphones, security cameras, text messages, audio files, shared documents, and youtube videos come together in a sort of collective flow of consciousness and a 3D space built through photogrammetry to create a common ground to gather all of the different voices, subjectivities and physical realities. In this project, other ways of relating to each other through space are collectively invented, bodies are absent and present at the same time. They move digitally through space in order to come together, altering the protocols that shaped our lockdowned lives and that still linger in our daily bodily interactions.

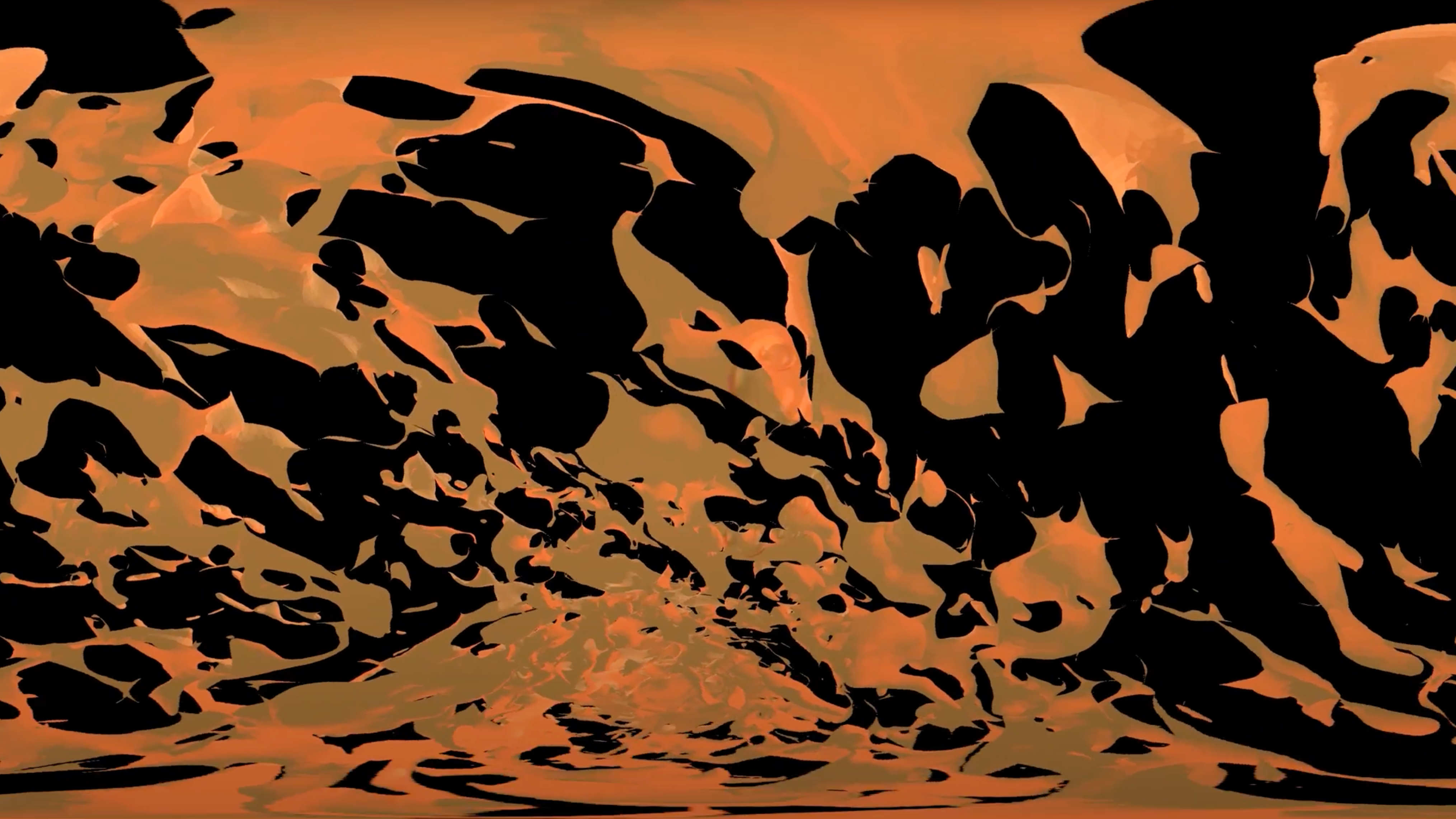

Chaveli Sifre, Smoke Compositions. A meditation on the history and materials of incense, video, 2022

Burning and smelling

Burning incense has been a part of religious rituals for centuries all over the world. Buddhism, Taoism and Shinto, Christianity, Hinduism, Islam, and Judaism all use different types of incense during ceremonies as a method of purifying the surroundings, cleansing the body, and bringing forth an assembly of buddhas, bodhisattvas, gods, demons, and the like. In the island of Santorini, where Chaveli Sifre started research for her work Smoke Compositions. A meditation on the history and materials of incense , incense is an important part of the Orthodox Christian service, meant to help the congregation engage fully and with all their senses during rituals, but also, as the Old Testament proclaims in Psalm 140, Verse 2: “Let my prayer be set forth before you as incense, the lifting up of my hands as the evening sacrifice,” the smell and smoke remind people that God is listening and that their prayers are lifted up to him “as incense.” Sifre explores human sensory experience as a form of relating to the world. One of the premises of sensory anthropology is that the senses interact with each other first, before they give us access to the world. Therefore, the way we perceive the world, its shapes, colors, spaces, but also ideology, religion and belief systems, invisible structures of spirituality, are all shaped by our senses. The olfactory sense, always relegated to the more functional senses of sight and hearing, plays an important role in cementing certain cultural rituals and hence, certain behaviors. However, Sifre believes that as much as the sense of smell has been able to engrain itself in the structured way we relate to the world, it can also remove us from ordinary ocularcentrism, and, in doing so, it offers us a glimpse into a different world—allowing us to enjoy, understand, and even generate other possible worlds.3

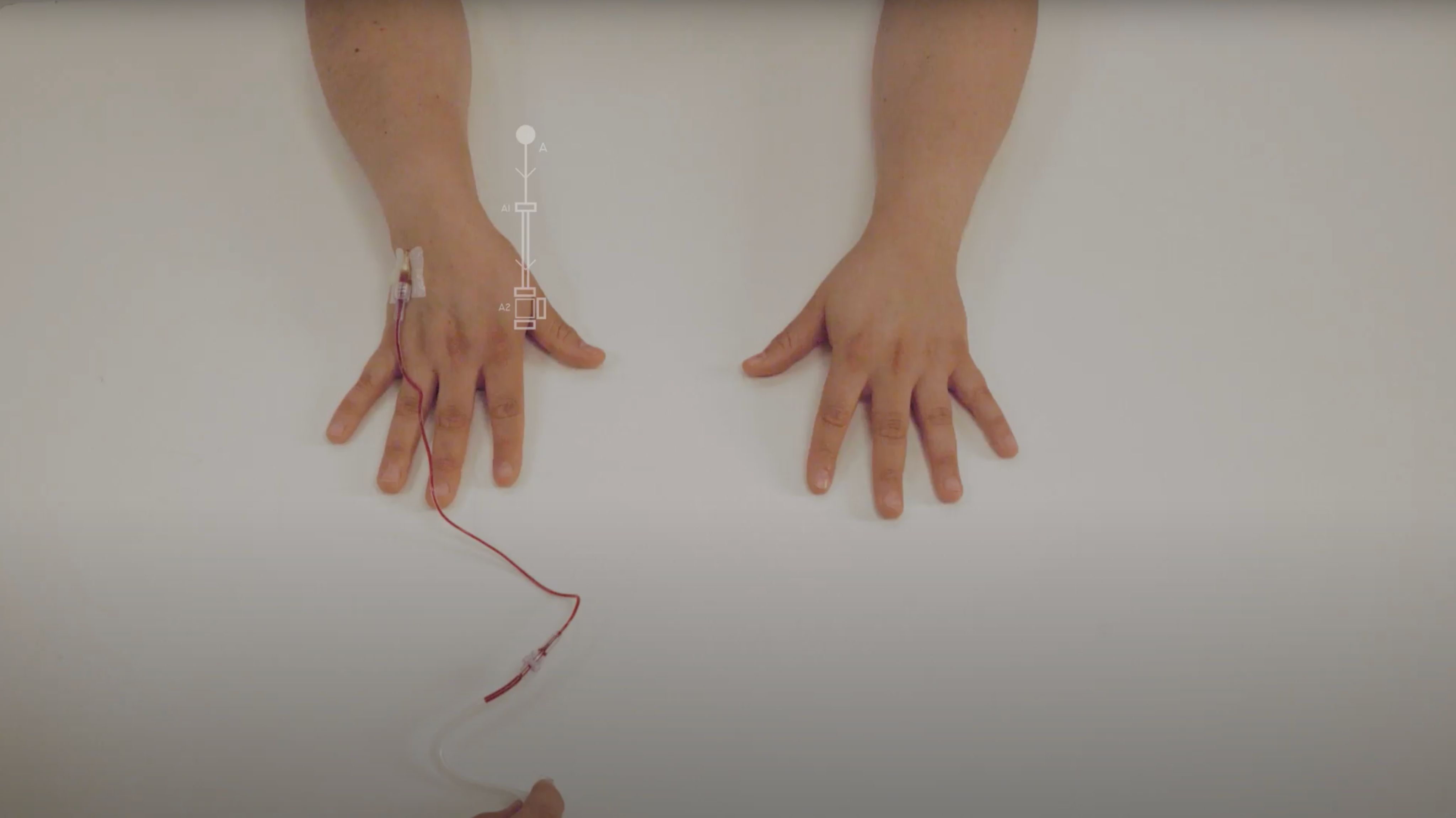

Ana María Gómez López, Diagram for Punctum v. 4), video, 2022

Re-arranging the body

Bodies are infrastructure themselves, they perform operations of strength and movement, they process substances necessary for its production and reproduction and turn it into energy, they also become technologies of circulation for bodily fluids and electricity. Ana María Gómez López, has been carrying out auto-experimentation on her own body since 2013, altering imperceptible physiological functions and those of the body parts involved in each of them, in conjunction with single-use medical devices, whose purpose is modified in the process as well. In Punctum, a series of iterations of an experiment in which she attaches an artificial extracorporeal circuit to herself, and lets the blood channelled from one of her arteries stream back into another vein thanks to the flow created by her own blood-pressure4. To create this external circuit she uses hypodermic needles, extension tubes and valve fixtures, commonly used in medical procedures. By connecting herself to this circuit Gómez López is bypassing the limits of her body as a sole autonomous organism, extending it through human made artifacts that become a part of herself for the duration of the experiment. The artist and researcher combines internal and external, human and non-human infrastructure to test the limits of these categories, momentarily becoming more-than-human by unifying vein and tubes into one continuous lumen. These corporeal interventions, as her other auto-experimentation experiences, transform, if only for a few days or even minutes, they way her body relates to itself and to its surroundings, posing questions about the boundaries of the body and the infinite possibilities that lay in its interactions with medical and other types of infrastructure. The final form of these works are “how-to guides” that allow other people to experience with themselves and in this way keep expanding the field of possibilities of human bodies-infrastructure relations.

Sofía Durrieu, Out of Order. App, app and video, 2022

Running your tongue along the inner part of your teeth

The construction of the invisible system that regulates our behavior is the result of centuries of conditioning, and of the imposition of categories and devices that organize the world according to modern-colonial structures of power. However, the fact that in the western world we shake hands when we meet, use forks and knives for eating, sit on chairs, keep all our bodily functions private, and generally respond obediently to instructions and rules that tell us how to move, interact and operate has become our normalized, “natural” behavior. Over time, these have become the only acceptable forms of relating to the world and to each other. Any attitude or gesture that is outside the norm is either pushed to the margins, completely vanished, or, in occasions, rapidly engulfed and set into the system as a trend or innovation within the acceptable parameters. Sofía Durrieu’s <b>Out of Order</b> project targets these learnt behaviors and attitudes and investigates ways of overloading and disrupting our internal systems through absurd or unexpected instructions such as “Run your tongue along the inner part of your teeth”, “Move your eyeballs”, “Smoke three cigarettes at the same time”, “Put one to three fingers near the mark on wall, make your head touch your knee”, or “Put both your feet next to the mark that’s on the floor, jump three times in a row, shout: Suzanne!!”. Through the imperative form of absurdity, humor and confusion, she startles us into consciousness about the way our bodies react to walls, stairs, or even to our own teeth. These instructions in the form of pamphlets, videos, and a free app are ultimately designed to provoke estrangement and awareness, based, as Durrieu proposes, on a “dialogue where connection, participation and free-willed mutual attendance are basic conditions for its existence”.

The absurdity, humor, and speculation of these four works and the experiences they offer the viewer-participant, propose radical displacements of the body within its existing contexts and conditions of living, while turning our attention to the absurdity of some of the objects, protocols, rules and material and immaterial infrastructure that run our lives. They leave us wondering whether other ways of living are possible and how to turn infrastructure into tools for asserting life instead of constriction devices of power.

1. Easterling, Keller (2014). Extrastatecraft: The Power of Infrastructure Space. London: Verso.

2. Barad, Karen (2007). Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham: Duke University Press.

3. Sifre, Chaveli (2021). Soft Power Towards a Museum for the Senses. Sensual Epistemologies Generated by Artists from the Global South. Master thesis, Hochschule für Technik und Wirtschaft, Belin.

4. Gómez López, Ana María (2020). "Anatomical Minutiae and Cannular Self-experimentation,” Performance Research, 25:3, 77-82, DOI: 10.1080/13528165.2020.1807764

Sofía Dourron (b. 1984, Argentina) is an independent curator and researcher. holds a BA in Art History and Management, an MA in Latin American Art History and was a participant in the De Appel Curatorial Programme 2018/2019. In 2019 she was an International Research Fellow at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art of Korea. Her recent projects include: Temporada Fulgor. Foto Estudio Luisita (Malba, 2021), Myths of the Near Future (Asia Culture Center, Gwangju, 2020), Landscape with Bear (De Appel, Amsterdam, 2019), Sin título. Elba Bairon (Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, 2017) and Avello: joven profesional multipropósito (Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires, Buenos Aires, 2017). She has contributed essays for publications on artists such as Joaquín Boz, Dignora Pastorello, Juan del Prete, Jorge Lezama, Edgardo Vigo, Hernán Soriano and Marta Minujín, amongst others. Dourron was part of La Ene, Nuevo Museo Energía de Arte Contemporáneo, which she directed between 2015 and 2018, and was a Curator at the Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires. She lives and works in Buenos Aires. Her current work researches the relationships between the Latin-American decolonial perspective, the notion of the decolonization of the unconscious, and artistic practices. She also continues her work on art institutions in Latin America, focusing on the paradigms of the museum as a colonial device, and designing alternative genealogies that scape the modern universalist canon.